Time may emerge from quantum entanglement with clocks

There is a fairly large group of physicists who believe that time is a statistical phenomenon like temperature and pressure. This is because time appears in a similar place in quantum statistics that temperature does in ordinary molecular statistics.

The concept is that time is emergent. If something is emergent, that means that it emerges from the sum of many parts, but you won’t find it in any individual part. The image of Van Gogh in this pointillist self-portrait is emergent.

No brushstroke contains the image, but together they construct a picture that is only rendered in our own minds.

Temperature is similar in that individual molecules have none. They have energy, but temperature is an average of the kinetic energy of many molecules taken together.

Recent research, published in Physical Review Letters, points to time being emergent from the quantum interaction between systems and their environment. Starting from a static quantum state, they were able to derive the time-dependent Schrodinger equation, which suggests that time can emerge from states where time is not there at all.

The parameter that becomes time in this derivation also becomes temperature if it is an imaginary number, which points to a mathematical connection between the two.

By partitioning their global system into a “system” and a “clock” as well as their interaction, they show how the entanglement between the system and the clock creates time.

How can this be?

In the paper, the authors, Gemshein and Rost, show how time emerges from a set of projections. A projection is a term for when you take a mathematical object in some number of dimensions and project it onto a space with a lower number of dimensions. Just as a bright light shining against your three-dimensional hands produces a bunny on a wall, a projection takes away information but also adds some. In this way, it removes the three-dimensional information of your hands while adding information about the light.

Thus, when a global state, representing the world of both system and clock but static with no concept of time, is projected against an environmental state representing a clock, you get a system state that is the global state evolving in time.

While the global state obeys certain symmetries that are completely independent of any parameters, the projected state obeys symmetries that are controlled by the parameter representing time, the tick of the ticking clock. This parameter is present in the clock.

Thus, the projected state, the result of the interaction between the global, timeless state and the clock, gains time.

The parameter that we call time can be given physical meaning now by relating it to motion. That is, the movement of a particle in the projected state as the parameter changes implies a physical definition of time.

The interaction between the global state and the clock is important because, without it, you could define separate “time” parameters in the projected state and the clock. Essentially, in a non-interacting system, the clock and system would not have to move at the same rate or mean the same things. Interaction forces them together. This may be why all parts of the universe share the same clock more or less and why quantum particles, when we observe them, appear to obey time with the same arrow that the rest of the universe follows (for the most part).

Is pinning time down as simple as proposing a quantum model by which it emerges from a static quantum state?

At best, it tells us how one can go from a static state to one that implies some kind of forward evolution. Yet, this model tells us nothing about why time has an arrow that travels in one direction. Nor does it explain our own perception of time as flowing from past to future.

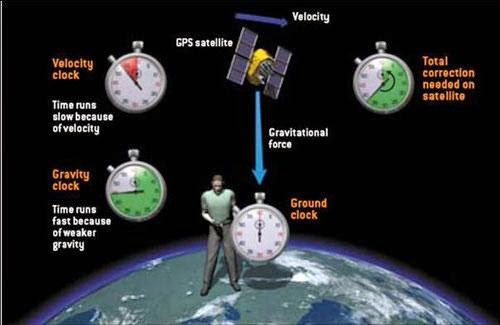

In General Relativity, Einstein’s theory, time is defined by gravity, which explains why one observer can have a different measure of time compared to another. This is why the Global Positioning System (GPS) that we all use every day has to account for the different rate at which time flows up in orbit than down on Earth. Without that correction, positions would be miles off.

The Einstein field equation, the equation of motion of General Relativity, can be written as evolution equations in time, or at least some parameter which we name t and give the name “time” to. The physical interpretation of this parameter, however, bears little resemblance to time in non-relativistic theory, such as that of Isaac Newton.

In Newton’s view, there is absolute time that reigns everywhere, and all clocks measure it. Thus, this time t in his theory is something that we can observe. It is an observable, in physics parlance.

In Einstein’s view, however, time t is not observable. Only our proper time, which is sometimes given the coordinate name “s”, is. When you read off the hands or digits of a clock, this is what you are observing: the time where you are, not global time t.

You see, t is just a label for a coordinate like x, y, or z for a spatial coordinate. It has no intrinsic meaning. In other words, it isn’t measurable except in an artificial way. This is both the blessing and the curse of General Relativity, called general covariance. It is a blessing in that we understand now that coordinate transformations have no physical meaning. They are mathematical, and anything that is observable must be invariant under such transformations. It is a curse because it removes the inherent measurability of time and space that we are able to maintain in non-relativistic and even special relativity (relativity without gravity).

Einstein himself found this very puzzling, and it took him many years to realize that general covariance is not a real symmetry of General Relativity. In fact, it was an artificial symmetry of coordinate systems that later mathematicians would remove completely from GR with the theory of differential forms, a coordinate-free way of understanding the theory.

Differential forms are like measuring devices, a mathematical gadget for giving you information about something. Think of a measuring tape. You provide a measuring tape with some length, say a two-by-four, and it spits out a single number. Differential forms are similar in this regard and come in various forms, depending on what they take in and what they produce.

A 1-form, for example, takes in a vector, some pointing direction, and gives you a number in much the same way a measuring tape gives you a number from a one-dimensional length.

A 2-form takes two vectors and gives you a number. Think of this as something used to measure the area of a rectangular room. Each side of the room is like a vector, and the 2-form is something that measures the room’s area by taking in those two sides.

A 3-form takes in three vectors, like measuring the cubic space of a room, and so on.

You can also have 0-forms, which are just numbers.

The beauty of differential forms is that they don’t operate in coordinate systems, so you never have to worry about whether some conclusion you are drawing is coordinate-dependent. This is important because coordinate dependence is often subtle and hard to detect. For example, some warp drive theories that travel faster than light have made the rounds in the news, only for others to argue that those solutions are coordinate-dependent. A coordinate-dependent conclusion is not real. It is an artificial observable.

When you look at general relativity using differential forms, you see that time as a global parameter does not exist. All you have are local times. The only reason you can understand time passing somewhere else is that something traversed the space between you, such as light. You can, for example, receive a signal from a distant clock that gives you its time and compare it with your clock. You can look at how the distant clock runs slower or faster than your own clock based on its velocity and gravitational field, in the same way we do with GPS satellites’ on-board atomic clocks.

So you might conclude from this that you should be able to define, at every point in spacetime, a clock and that all these clocks taken together define some global time, maybe not one clock to rule them all as in Newtonian theory, but a multi-clock theory. But you would be wrong. The reason you would be wrong is that observers at the precise same location, even if they experience the same gravitational field as each other, may be travelling at different velocities, in which case their clocks will run at different speeds.

Even worse, observers at the same location could be undergoing different accelerations, which, because acceleration is indistinguishable from a gravitational field, would argue that they have different gravitational fields!

While you could restrict your clocks to only observers in free fall, which is an objectively measurable condition, that would exclude every clock on Earth, since only clocks in orbit are in free fall for any appreciable length of time.

Thus, you can’t define a universal, global time coordinate using just local clocks. You must define a coordinate system that specifies how fast each local clock is running and in which direction, and what the gravitational field is, including accelerations.

Quantum mechanics, meanwhile, sweeps away all these problems and presents time as Isaac Newton did, an external tick that keeps everything going forward. In fact, time isn’t even an observable in quantum physics. It’s literally just a number. Meanwhile, positions are treated as infinite-dimensional vectors in a mathematical space called a Hilbert space.

This is why quantum theory and gravity are irreconcilable.

In fact, the reason we have no theory of quantum gravity is primarily because we have two fundamentally opposed theories of time, one where time is purely a local phenomenon defined by clocks and observer state, and one where time is absolute and external.

And even in the case where we try to derive time from a timeless quantum state. The time we derive is that absolute, external time.

Despite being absolute, however, quantum mechanics plays games with time that would make Isaac Newton’s head spin.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Infinite Universe to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.