The dominant model of cosmology may be falling apart

Challenges to the ΛCDM can no longer be ignored

To paraphrase Mark Twain, the death of the ΛCDM has been greatly exaggerated. The dominant model of cosmology, which proposes a cosmological constant, Λ, to explain dark energy and a “cold” dust-like version of dark matter called CDM, has withstood many attempts to dislodge it from its perch. Most astrophysicists acknowledge, however, that the model merely sweeps the physical unknowns under the rug in favor of highlighting certain mathematical choices in our cosmological models. After all, the model does not tell us what the cosmological constant is or where it comes from, simply that it is constant. Nor does it explain what dark matter could be, although there are many, many guesses. All it says is that it is not at all radiation-like but rather like ordinary, massive dust particles that nevertheless fail to interact with anything electromagnetically.

This is the natural progress of science. When Kepler proposed his laws of planetary motion, he had no idea what kept the planets in their orbits, nor did he connect it to what makes objects fall down on Earth. When Newton proposed his inverse square law of universal gravitation, he could not explain what caused the force, why it appears to be instantaneous (it is not), nor even why planets remained in their orbits despite all interacting with one another.

Science is always semi-empirical, discovering models that explain what we observe first and only later matching them to theory, which hopefully drives us to observe yet more subtle effects.

Hence, it was only a matter of time before new observations and new tools poked holes in the ΛCDM, and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and other recent experiments have done just that.

What we are discovering is that the dark sector, that which we do not know about the universe, is much more complex than we have believed until now, and like Kepler’s laws, which only apply to two-body motion, hid the real complexities of N-body Newtonian motion, the ΛCDM has veiled the real complexity of the invisible.

Consider studies of dark energy; while early studies of dark energy largely confirmed ΛCDM, more recent ones have called it into question.

First, there is the Hubble constant tension, which has only worsened with time. Hubble’s constant refers to the present-day measurement of Hubble’s parameter, which itself changes over the history of the universe. The tension refers to disagreement between measurements of Hubble’s constant from early universe observations related to Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) data and the later universe using type 1a supernovae, as well as other reliable distance measurements. These observations suggest that, at best, Hubble’s constant may either not be constant everywhere in the present universe or that the cosmological constant changed from the early to the later universe.

While many astrophysicists attempt to find measurement errors that could explain the tension, so far, there have been none found, and different methods and observations, completely decoupled and unrelated to one another, all show the same discrepancy. For example, distance measurements are needed to determine Hubble’s parameter in the later universe. There are different ways of doing this, some of which are completely decoupled from one another, meaning one does not depend on the other. Typically, distance is determined by observing stellar objects that have a known brightness. For example, Tip of the Red Giant Branch (TRGB) and type 1a supernovae both fall into this category, but both disagree with the CMB.

Measurements from the largest and most precise dark energy survey ever performed, Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), meanwhile, have suggested that the ΛCDM is somewhere between 2.8 and 4.2 sigma unlikely to be correct. This is extremely unlikely (less than 0.3%).

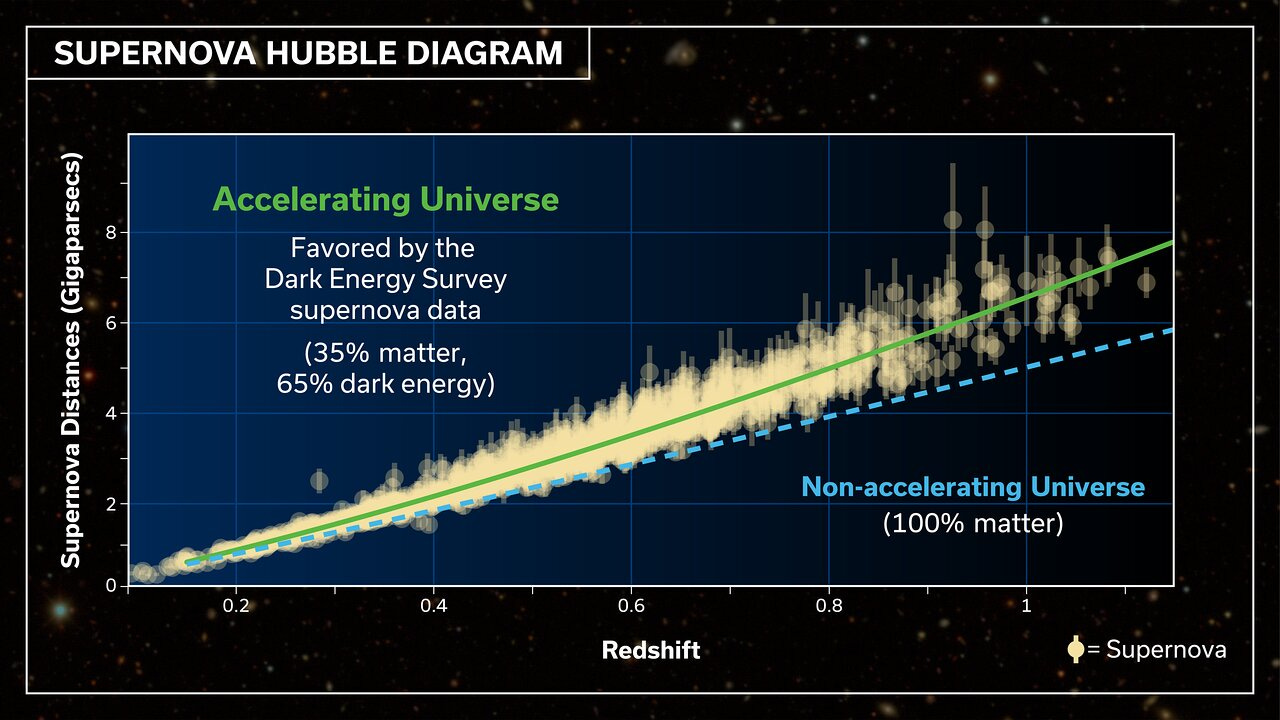

DESI measures things like type 1a supernovae and Baryon Acoustic Oscillations (BAOs). Type 1a supernovae are simply supernovae that occur in other galaxies that have a very particular brightness. This allows us to determine how far away they are, which, combined with measuring redshift of the galaxies they are in, lets us build redshift-distance correlation charts for the universe at different points in its history. This is how we know that the expansion of the universe is accelerating:

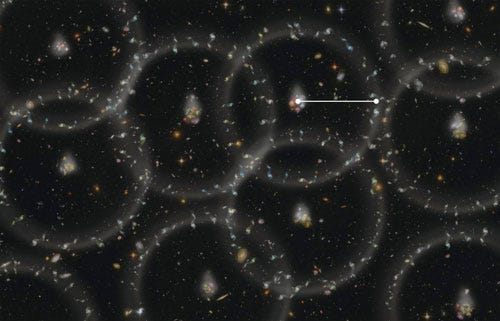

BAOs, meanwhile, are measurements of oscillations in the distribution of galaxies caused by primordial plasma like sound waves that echoed through the universe from that early, hot, dense period. These provide another way to measure the history of the expansion of the universe, separate from supernovae. Essentially, these are like ripples of baryons (ordinary matter) that expand out in a spherical wave from clumps of dark matter. These spherical shells expand along with the universe, and so we can observe them at different distances to get an idea of how the universe has expanded.

The big problems DESI has found are discrepancies between the history of the expansion of the universe when looking at BAO, supernovae, and the CMB. Instead of a cosmological constant, a dynamical dark energy fits the data much better. There is even a suggestion that dark energy went through a “phantom” phase about 5 billion years ago. In a typical cosmological constant model, the pressure of the universe is equal to the negative of the density. This is often written as w=-1, where w is that ratio. A phantom state is where the magnitude of the pressure in the universe is larger than the density, i.e., w < -1.

This could potentially cause the expansion to accelerate so much that the Big Rip occurs, where all structures in the universe tear apart all the way down to atomic nuclei.

Whether this was ever a real risk, DESI data suggest that dark energy is indeed dynamical. Besides the phantom phase 5 billion years ago, dark energy appeared to fluctuate wildly before about 8 billion years ago.

These fluctuations plus the phantom phase would suggest a far more complex dark energy model than even simple quintessence (minimally coupled scalar field).

Unfortunately, the best dynamical dark energy models fail to solve the Hubble tension. They even make it worse!

If this shows anything, it is that gambling on dark energy research, which by no means was clearly going to pay off 20 years ago when the initial investments were made in things like DESI, has paid off handsomely. Considering that the Large Hadron Collider was a $5 billion investment that has failed to find anything beyond the Standard Model, DESI cost less than $100 million to build, and it is already poking holes in our best models. While JWST was a much larger investment at $10 billion, it appears as though it will be paying off for years to come in many different areas of astronomy and astrophysics.

What will the future hold? Perhaps we will find that there is more than one kind of dark energy or dark matter. Perhaps general relativity will finally be corrected. The history of the universe may be more like the history of the Earth, with vast geological ages very different from our own, than it is like high-energy physics, where “simple” models can explain everything we can observe. With all this going on, it is a great time to be alive.

Leauthaud, Alexie, and Adam Riess. "Looking beyond lambda." Nature Astronomy 9.8 (2025): 1123-1128.