I came across a recent video by physicist Sabine Hossenfelder in which she argues that human beings have no free will. She further argues that physics explains “us” and how we work because humans are “big bags of particles”.

She claims that the idea that the mind is greater than the sum of the particles of our bodies is “in conflict” with what we know, and even if it were, other laws would simply govern emergent reality.

We know from physics that all laws are either deterministic or random, meaning that we have no control over them.

She argues that there is nothing “special” going on in the human brain that a “computer can’t simulate”.

She insists that we need to “accept that the human brain is a machine”.

But her assertions are full of logical holes.

While Hossenfelder and I are both professional physicists, we have somehow come to different conclusions about the nature of reality. Did we have the freedom to choose our beliefs? According to her, no. According to me, kind of.

It all comes down to philosophy.

Her philosophy is neither new nor exceptional but rather based on certain unspoken assumptions about the world and how it works. It ignores uncomfortable truths about the human mind to try to reduce the mind to mere cause and effect and make it more machine-like.

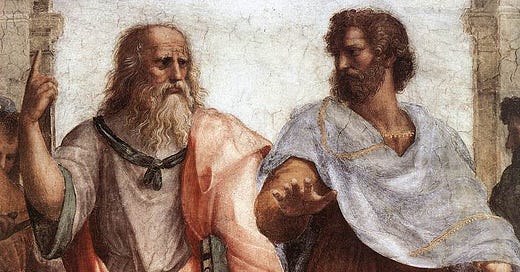

Dr. Hossenfelder’s argument goes back to 18th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who attempted to create an entirely materialist philosophy. Hobbes, however, struggled with the philosophy of mind and attempted to sweep it under the rug, which is what Hossenfelder, likewise, is obliged to do.

While she dismisses physicalism and scientism as “just words”, they do have meaning in the sense that once you accept that the universe is entirely material, physical, and guided only by natural processes, you are forced to accept that certain concepts that we depend on for our cognition are illusions.

And these are not small concepts. They include logic, including any statement that has a truth value, true or false, even mathematical statements like 1+1=2. Morality, right and wrong, also cannot exist in her material universe except as evolutionary adaptations. Feelings like love are merely electrochemical states in our brains. Even your existential dread is just more chemicals.

Consciousness itself must be explained in some way, too, because we can’t deny it exists. In her worldview, consciousness is, however, an illusion too, as the late materialist philosopher Daniel Dennett often ludicrously asserted.

Interestingly, Dr. Hossenfelder avers that there is no evidence for anything beyond the material, yet no philosopher has successfully explained how the mind can be so. Every philosopher who has tried has had to dismiss the mind as irrelevant, a fiction. At best, a physicist or other scientist, such as a neuroscientist, can point to certain configurations of the brain and explain that these are responsible for the perception of the color red, the smell of a rose, the feeling you get when you see a loved one after a long absence.

Yet, these are not those feelings themselves. After all, if a computer could simulate a brain perfectly, every neural behavior, would we be able to say confidently that it knows what those feelings are? Or is it just blindly operating on numbers with no conscious awareness?

This is known as the “knowledge argument” or “Mary’s Room,” a thought experiment proposed by Frank Jackson.

If Mary, a scientist, knows everything about perceiving a color, is it the same as experiencing it herself?

Most people would say no, yet this is precisely what we mean when we talk about AI simulating the human brain. At best, the AI can know everything about how the brain perceives color by being trained on, say, brain scans, but that doesn’t mean it can also perceive that color. There is no way to train AI on the experience of anything because we cannot reduce such experiences to data. No matter how effective or superhuman AI becomes, we will never know if it experiences anything! We only infer that other people do because we assume they are like us.

It seems intuitively obvious that being able to simulate the perception of a thing is not the same as the perception of that thing. Hossenfelder’s denial of a non-material source for consciousness and other immaterial parts of our minds does not resolve the issue but creates more issues.

The statement “there is no evidence for anything beyond the material” isn’t verifiably true for several reasons.

True and false values for statements are themselves immaterial, so one implicitly acknowledges the immaterial to even address it.

The concept of “evidence” as a reason for believing something is true is also an immaterial thing. No immaterial, no science at all.

There are certain things we experience where we don’t know if they are material or not, like the afore-mentioned conscious experience. I.e., there is no evidence that these things are material.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Infinite Universe to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.