Climate change may be causing more cold snaps but not for the reason you've been told

Why polar vortex stretching, not disruption, is giving us more winter headaches.

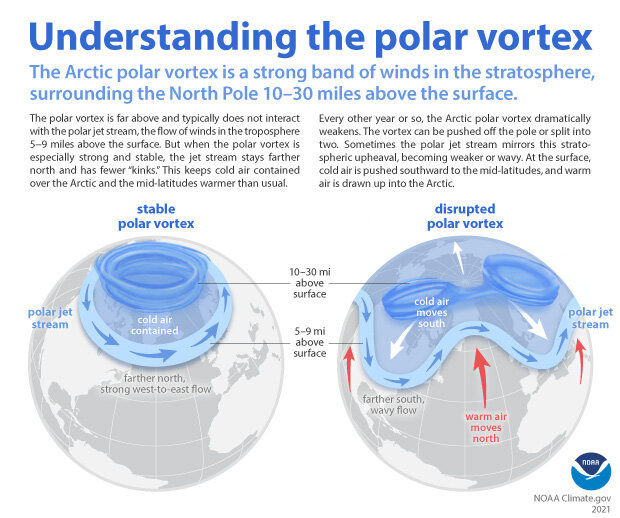

You might have seen this graphic floating around social media, showing a disruption to the polar vortex causing cold snaps.

The culprit: sea ice melting from global warming.

At least, that’s what social media is saying.

Scientists, on the other hand, are puzzled by the conflicting data. In some models, the cause is sea ice melting in the Arctic. But other models show confusing predictions about what is happening. A well-cited review article says:

In model experiments, sea ice loss in the Atlantic sector appears to cause a weaker vortex, whereas a stronger vortex is found in response to sea ice loss in the Pacific sector

What is clear is that the polar vortex has been weakening for decades, and we know sea ice has been melting too. Shouldn’t the two be correlated?

Almost certainly, but that doesn’t establish a causal relationship between the two, and the models seem to bear out that the answer is much more complex than we would like.

Even further complicating matters is that scientists aren’t sure whether polar vortex weakening is caused by global warming at all.

That same review article mentions two studies from 2017 that attribute the weakening to “internal variability,” which causes Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW), the immediate cause of the weakening.

The reason is that models show that, while the vortex does respond to climate change, the response is small compared to normal variability in the strength of the vortex.

How do we know that the vortex wouldn’t have weakened mostly without global warming? Perhaps the effect of warming is actually negligible.

This is the problem with a lot of studies of climate change. The climate has always changed. How do we separate the effects caused or exacerbated by global warming from those that are unrelated?

It’s not enough to show a causal relationship between warming and a particular effect. What if that causal relationship is weaker than observed and the overarching cause is something unrelated to warming?

Indeed, more model-based studies are showing that global warming and sea ice melting may not be the culprit at all. Some models show sea ice loss strengthening the polar vortex later this century.

So what’s going on?

In this article, I want to explore the research that has been done on the polar vortex, go beyond what news outlets will tell you, and get to the heart of why this question is so complex and currently unanswered.

The polar vortex starts in autumn as the Arctic cools. It is a stable westerly wind high in the stratosphere driven by the rotation of the Earth. It is symmetric and typically circular.

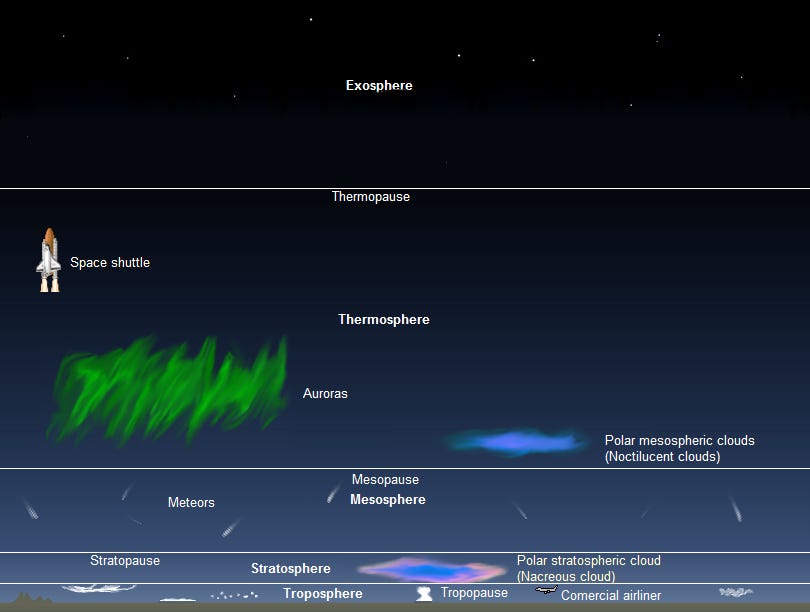

The stratosphere is the layer of the atmosphere directly above the layer in which we live. It is where jet airliners fly.

The vortex is usually stable. Some graphics depict it as a kind of corral that keeps all the nasty Arctic cold in the Arctic and away from us. That is not quite true. It’s more the other way around. The polar vortex surrounds the cold air in the Arctic that forms in winter.

Sometimes the troposphere, where we live, sends warm air upward into the stratosphere, causing it to warm up.

These SSWs happen about every other year. Sixteen such events were observed between 1998 and 2024, although the criteria for identifying them have evolved somewhat.

Most models show, however, that while the polar vortex will weaken with climate change, that does not lead to an increase in SSW events. One model looked at 1000 years of pre-industrial SSWs and showed that they work on 60 to 90-year cycles, “which is associated with long-term variability in the amplitude of the quasibiennial oscillation (QBO)”.

The QBO is a 28 to 29-month oscillation in tropical stratospheric winds. It has both a positive and a negative phase.

During the positive phase, the northern United States in winter becomes cooler than normal, while the Upper Midwest, Rockies, and California are wetter than normal. The South and East become drier than normal.

During the negative phase, the lower 48 of the United States is likely to be cooler than normal in winter, especially in Texas, where I currently live. Meanwhile, the Rockies, plains, and Ohio Valley are drier than normal, while the South is wetter.

If the QBO is the main driver of SSW events, then polar vortex weakening, even if driven by climate change, might not be causing cold snaps in the United States.

And while the northern hemisphere vortex is expected to weaken, its southern hemispheric counterpart is expected to strengthen with climate change.

Another source of cold snaps is caused not by SSW or polar vortex disruptions, but by a stretching of the polar vortex into an oval shape. The 2021 Texas cold snap that caused so much misery, for example, can be linked to such a stretching event in February, which followed an SSW in January.

Sea ice loss seems to modulate the stretching, changing the timing of the effects and also causing them. Sea ice loss causes snowfall to increase at high latitudes because there is more exposed ocean to evaporate into the air. Indeed, snow increase seems to be a better predictor of stretching events than sea ice loss.

Indeed, unlike SSWs, stretching events have much more of a close link to climate change.

As the sea ice melts and snow increases, the exchange of heat between the troposphere and the stratosphere changes as well.

What this means is that sometimes cold snaps are likely to increase because of climate change. In particular, ocean warming in the Arctic causes sea ice loss, which may not raise sea levels (ice floating in the water can’t), but it can cause more cold snaps in winter.

The relationship between sea ice, snow, and polar vortex stretching events is somewhat complex, so I won’t go into it. Also, the debate over how to separate the signal from the noise in the climate continues. While some researchers are very confident in the link between climate change and polar vortex changes, others are more cautious because of the potential for cyclical changes. Models sometimes disagree on findings.

That there are negative impacts from climate change is clear, particularly changes in the Arctic, which is warming far more rapidly than the rest of the globe. What the ultimate result of those impacts will be is hard to see. Eventually, there may be no Arctic sea ice at all, which could cause other changes to accelerate.

As I discuss in the bonus content below, we have had success in coming together to agree to stop climate change issues before, with the banning of CFCs. Unfortunately, climate change is a much, much bigger problem. One cannot simply undo the Industrial Revolution, and the promises that “new” technologies like electric cars will sort that all out tend to sweep away serious issues. I think it is important, however, to maintain a nuanced view about what these effects are and the unintended consequences of some heavy-handed attempts to solve climate change.

As individuals, we can at most saner voices heard above the shrill voices of those seeking merely to gain attention or vent their emotions.